My Garden’s Boundaries Are the Horizon

14:00–20:00

Opening: Vrijdag 6 december, 17:00-20:00 uur

de Appel, Tolstraat 160, Amsterdam

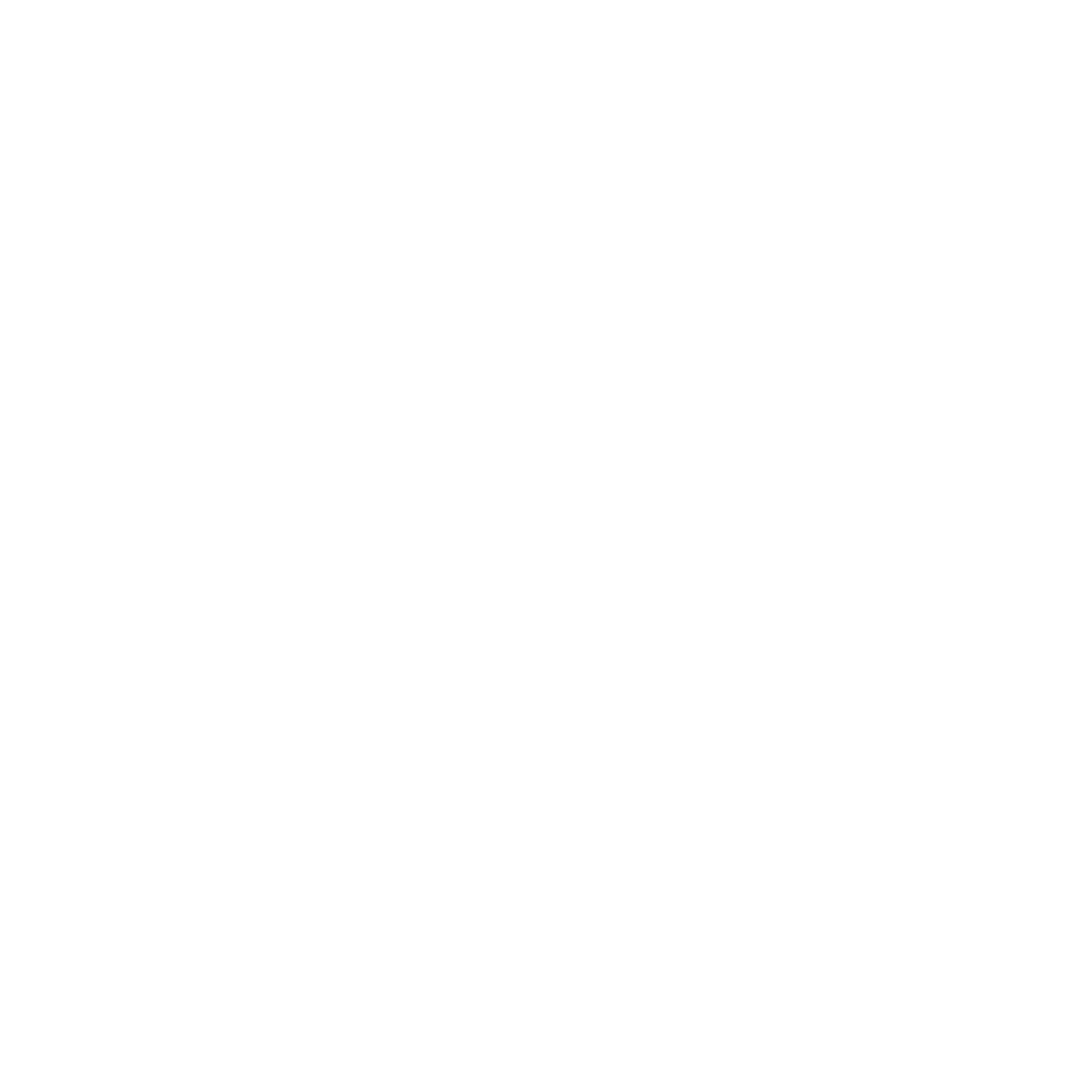

Qajar kushk, Fin Garden, Kashan, Iran. Photo: Diego Delso, Licensed under Creative Commons.

To See the Inability to See — a collective that formed at de Appel's Archive in 2019 — is known for their collectively written texts and their performative readings of a series of temporarily made triangular books. In 2022 and 2023 they developed a foldable multidirectional book/object called My Garden’s Boundaries Are the Horizon: A Porous Reader to Unguard the Garden. This publication has sculptural and performative qualities, stressing the relationship between bodies and books; provoking collectivity in writing, reading and thinking. It has been developed in close conversation with its designer, Elisabeth Klement, who joined their collective process by designing the book parallel to the development of its content. The book/object has now unfolded into the exhibition My Garden’s Boundaries Are the Horizon — a repertoire of objects, gestures and events that expands its content into the space and in relation to other bodies, such as those of readers, visitors and artworks. This unfolding takes place on a flexible sculpture display that also holds a selection of works, weaving the publication, the artworks and the artifacts into an inter-related constellation of physical and spatial experiences.

To See the Inability to See’s collective writing rises from an effort to open up spaces, question borders and establish new connections between objects and stories. In My Garden’s Boundaries Are the Horizon the artists look into power structures related to conventional forms of archiving and collecting. They see this archiving as a state of mind that we all experience on a daily basis: clinging to ‘the known’ and resisting change, ‘the unknown’, or the uncategorisable. For this publication the collective departed from (fictional) stories surrounding certain traditional Iranian buildings, such as the Persian garden called Fin Garden in Kashan, and in particular an octagonal vestibule called the hashti. The women-led uprising in Iran in 2022, triggered secret correspondences between the members of the collective, that turned out to have a big influence on the content of the book.

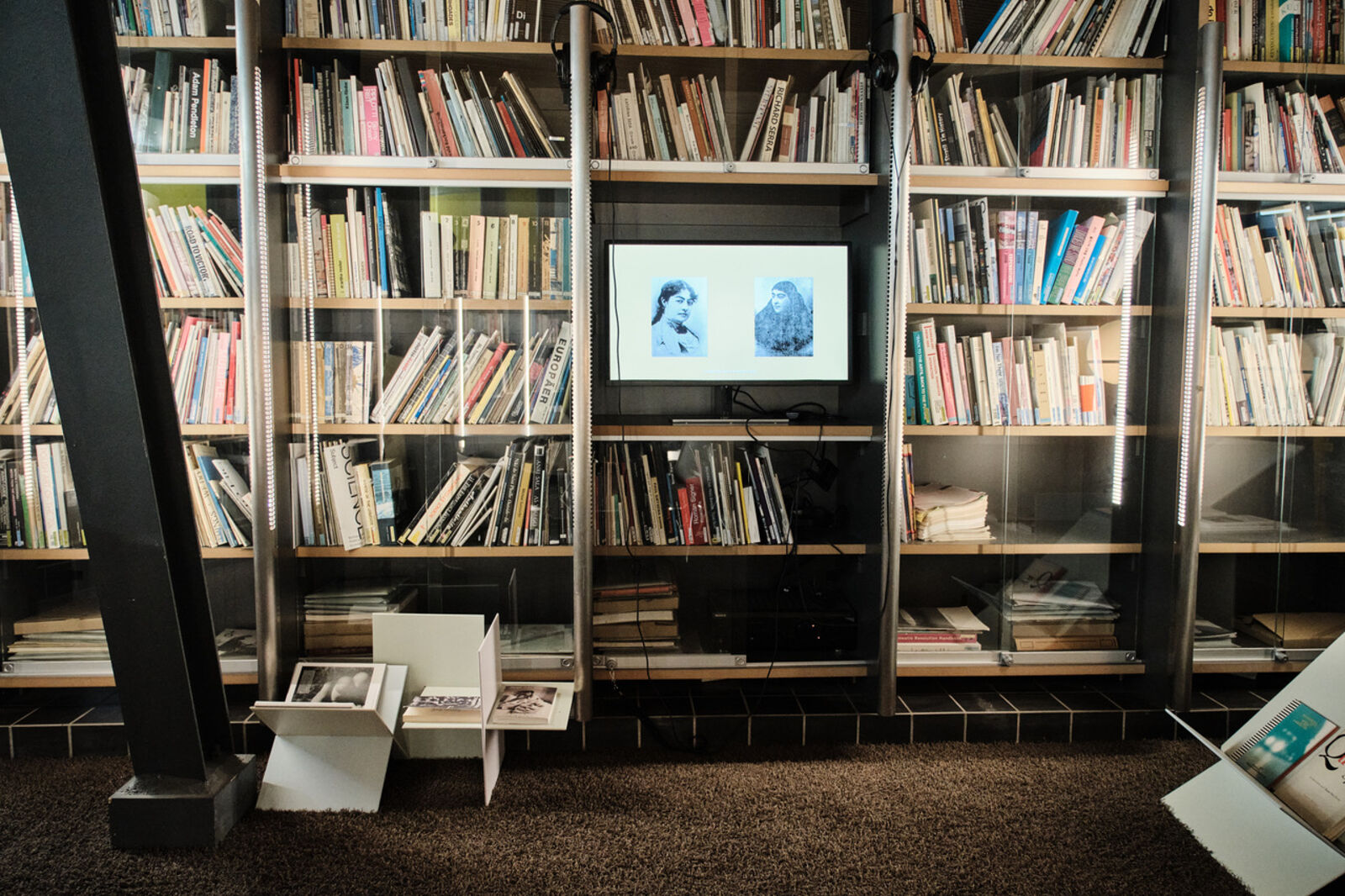

The exhibition encompasses different realms. One consists of artworks by the individual members of the collective developed alongside and parallel to the process of writing. A second realm includes historical objects from personal collections that are related to the content of the publication. A third realm comprises other artists’ works referenced in, or connected to the book. A fourth direction draws connections between the content of My Garden’s Boundaries Are the Horizon and de Appel's Archive, as it is from this archive that To See the Inability to See first started writing on visibility and invisibility, inclusion and exclusion in archiving practices. The title is a direct quote from Derek Jarman, referring to his fenceless garden at Dungeness.

Featured in the show are works by Arefeh Riahi, Martín La Roche Contreras, Maartje Fliervoet, Kader Attia, Kasra Jalilipour and Seba Calfuqueo, as well as a selection of historical objects.

During the exhibition there will be a public programme with film and video screenings by Derek Jarman, Kasra Jalilipour, Marcela Moraga and more titles to be announced, and performative readings with dash (-) collective, Constanza Mendoza, Giles Bailey, Lara Khaldi and Francisca Khamis Giacoman. The screenings are organised in collaboration with Kriterion.

This project has been made possible by: Cultuurfonds, AFK, TextielLab, Mondriaan Fonds.

The artists and de Appel wish to thank: Bronwen Jones (for her advice and assistance for the finish of Spilleages), Nicholas Martin and NYU Fales Library & Special Collections (for the support with the David Wojnarowicz’s Magic Box research), Josilda da Conceição and Mertens Frames (for their help in the production of Legitimate Pavilion), Mohammad Reza Riahi (for his generous lending of pieces from his collection), Marco van der Bilt (for the production of Multi-fold-object), Henriëtte Schaeffers.

Public programme

○ Friday 6 December, 5-8pm: Opening event

○ Wednesday 11 December, 6pm: Reading of and conversation about My Garden’s Boundaries Are the Horizon by dash(-)collective (info and tickets)

○ Sunday 12 January, 7.15pm: Film screening at Filmtheater Kriterion: Schutz der Sinne (2010) + Who's Afraid of Ideology Part 1 & 4 (2017, 2023)

○ Friday 24 January, 6pm: Reading of and conversation about My Garden’s Boundaries Are the Horizon by Constanza Mendoza and Giles Bailey (info and tickets)

○ Friday 7 February, 6pm: Performative reading by To See the Inability to See (info and tickets)

○ Friday 28 February, 6pm: Reading and conversation with Lara Khaldi and Francisca Khamis Giacoman (info and tickets)

○ Sunday 9 March, 7.15pm: Film screening at Filmtheater Kriterion: The Garden (1990) + short film (info and tickets)

○ Saturday 22 March, 6pm: Closing event: performative reading by To See the Inability to See (info and reservation)

Ticket and reservation links will be published here.

About the artworks and artists

To See the Inability to See is an artist collective with roots in Chile, Iran and the Netherlands. Through an essayistic and performative process, we weave stories, thoughts and visual material together with books and objects, allowing them to narrate a new story. We use this narrative to challenge ‘archival’ modes of thinking. Among our main topics of concern are exclusion, alienation and belonging. The physical form for the publication My Garden’s Boundaries are the Horizon was devised during, rather than after our writing. Its shape is based upon Arefeh’s Multi-fold-object series. The publication's design was developed in synchronicity with the narratives, writings and visual materials. The final object is a testament to the shared journeys we took together with the publication’s designer. We found in Elisabeth a collaborator who was open to our open-ended way of working. Elisabeth Klement is an Estonian graphic designer, educator, curator and organiser living and working in Amsterdam. As a graphic designer, she leads a practice rooted in design justice and collectivity. Thinking along with the project, she used fonts designed by women in both the Latin and Arabic alphabet.

Our collective projects resonate with our individual practices, and vice versa. For instance, Arefeh’s project The House of Secrets in Geometric Structures focuses on the complex power dynamic between public and private space, and more specifically the tension between genders within these spaces. In terms of its content, this work has formed one of the starting points for our publication. Through an investigation on traditional architecture of Iranian houses, and their modality of dividing spaces into public, semi-public and private, Arefeh questions the hierarchy of social relations. The main focus of the research is on an octagonal entrance room called the hashti: the mediator between inside and outside, and the connector of different spaces inside the house.

With a focus on the archive in its most expansive sense, Arefeh Riahi’s artistic research delves into non-archival modes of knowledge-making. In her interdisciplinary practice, she weaves narrative and performance to uncover the potential of ephemeral fictions — spaces of possibility shaped by what is termed the anarchive. The anarchive could serve to interrupt dominant orders, dismantle the singularity of thought, or function as a space for resistance.

Following the uprising in Iran, and reflecting on various forms of resistance, To resist is to remain invisible by Kader Attia came to be influential to our writings. This piece from 2011 was created during the Arab Spring, with which it contrasts: at the time, the act of resistance was to go into the streets, as millions did, and so to be visible. But insurrection is a point of departure, and true resistance begins in everyday life. It is a relentless resiliency that almost self-effaces itself as it becomes unconscious: resisting is natural, not only cultural. Resistance inserts itself in the daily cogs of the system to make it crumble from within.

Kader Attia is a multidisciplinary artist who draws upon the lived experiences of two disparate cultural identities: Algerian and French. From this place of cultural intermediacy, Attia’s practice interrogates socio-political complexities rooted in histories of colonialism and cultural obfuscation. In his practice, Attia develops poetic/political installations and sculptural assemblages to investigate the far-reaching emotional implications of western cultural hegemony and colonial systems of power for non-western subjectivities, focusing particularly on collective trauma and notions of repair.

In synchronicity with the theme of collective memory and the archive, Martín La Roche Contreras’ works often find their starting points from existing collections of objects and archives as modes of storytelling, which he reassembles into installations, performances or publications. In his participatory practice the listener-viewer is invited to complete the piece or engage with it. Through ephemera and anecdotes, individual stories are reappropriated and understood as part of a larger collective memory. In 2017 he initiated the Musée Légitime, a museum inside a hat, which he wears to carry its collection into different realms.

For My Garden’s Boundaries are the Horizon, Martín wrote about gardens and queer space, including references to Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage in Dungeness and David Wojnarowicz’s unique collection of objects, commonly referred to as the Magic Box. Martín’s Magic Box (after David Wojnarowicz) speculates about the stories contained within this collection of objects, currently housed in NYU’s Downtown Collection at the Fales Library and Special Collections. This box, discovered beneath the artist’s bed in New York after his passing due to AIDS-related complications in 1992, remains an enigmatic artefact with its contents left unaddressed by Wojnarowicz during his lifetime. For the show, Martín made an archive work by selecting and organising analogue second hand items from the 80s and self made reinterpretations of David Wojnarowicz’s objects brought together as a new collection. These are displayed alongside moments of performative unfolding and storytelling.

Our writings on hidden, destroyed and repurposed archives led to the creation of the piece Legitimate Pavilion. This installation by Martín was made with recycled paper from his 10-year archive of ephemera collected from other artists' exhibitions, including brochures, exhibition sheets, catalogues, postcards, and more. Following the shogi technique, Martín transformed this paper archive into partition screens inside the exhibition space, providing an intimate reading room for Arefeh’s work Unspeakable Secrets: a letter-essay, one of the components of The House of Secrets in Geometric Structures. This private letter — written to be shared with the public — reflects on the boundaries between private and public within a relationship. While hinting at unspoken secrets, it questions traditional structures of the home, culture, and relationships.

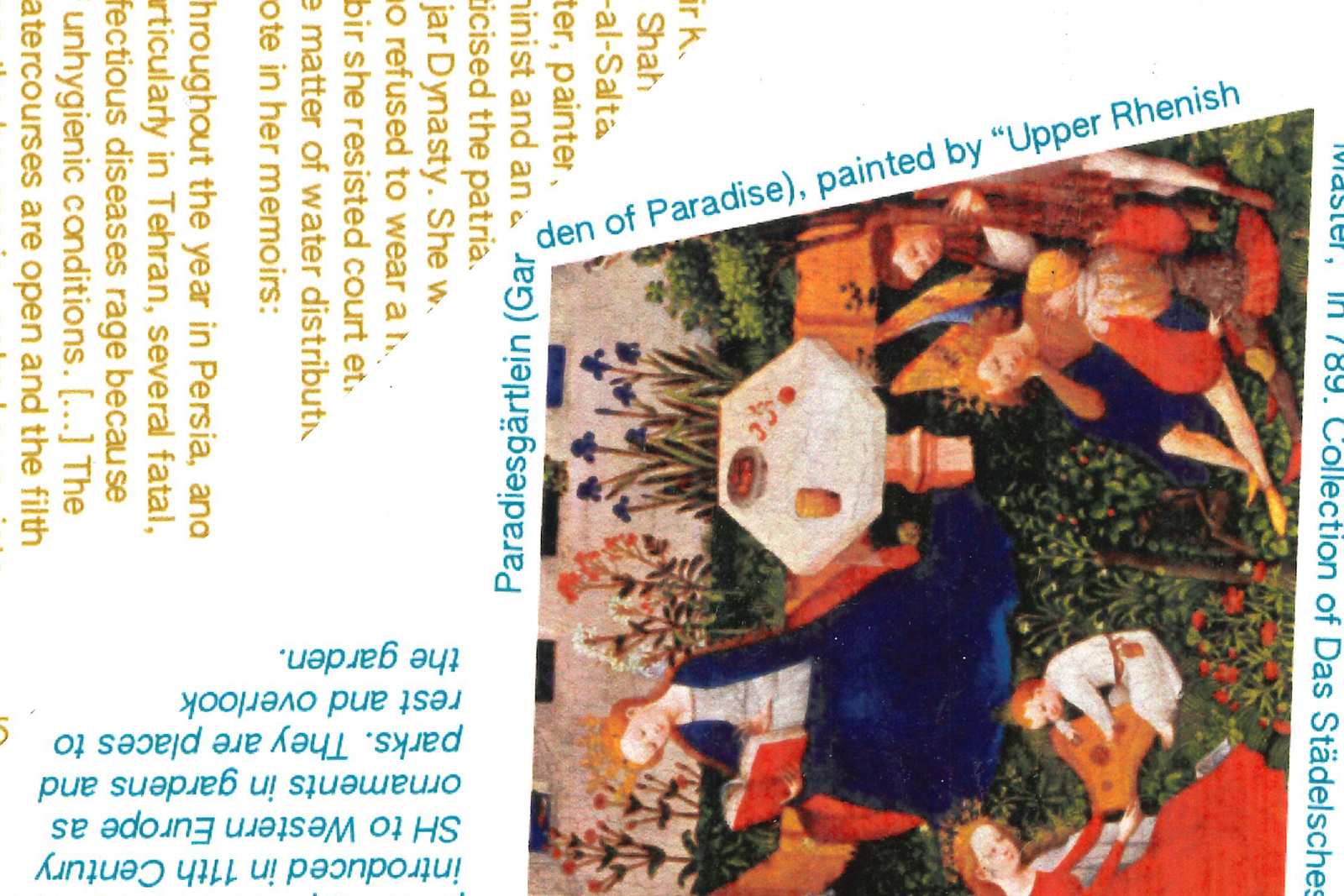

Another artwork that became part of our conversations is Gut Feelings: Fragments of Truth, a video essay by Kasra Jalilipour, an Iranian multidisciplinary artist based in Derbyshire, UK. They work in a variety of mediums including sculpture, works on paper, moving images and live performance. Through looking at histories and speculative fiction, their work takes on the role of recreating archival histories of queerness and transness, and at times they do this by looking at how religion and past cultures intersect with these often unarchived histories. Gut Feelings: Fragments of Truth asks how fragments of historical truth might help us to reimagine queerness in pre-westernized Iran. At its centre is Tāj al-Saltaneh (1884-1936), a member of the Qajar dynasty and feminist activist who in the age of the internet is frequently misrepresented and has become the subject of cruel memes. Fragments of Truth offers a queer and intersectional viewpoint of what has been documented of Tāj's life and the Qajar era.

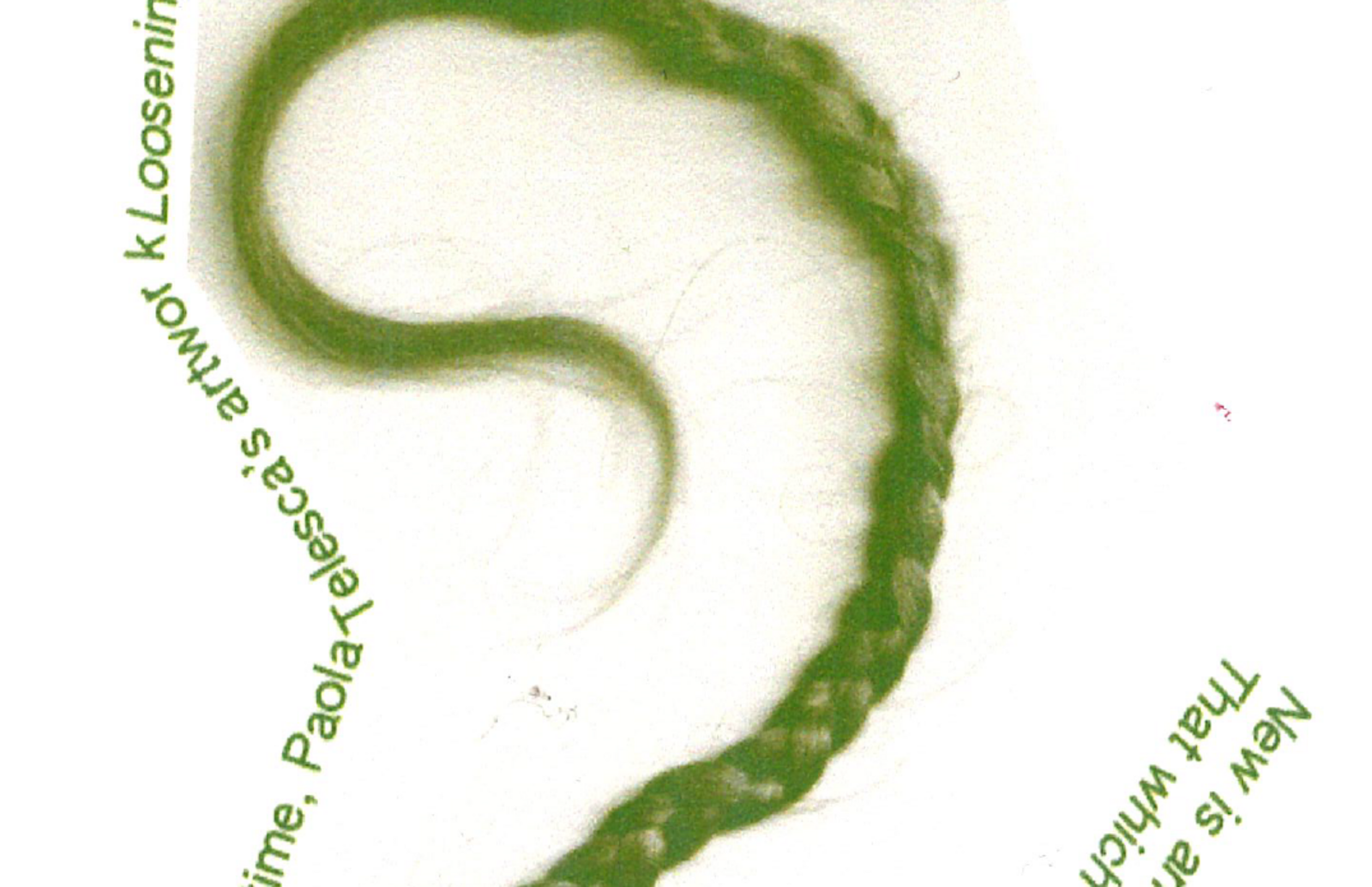

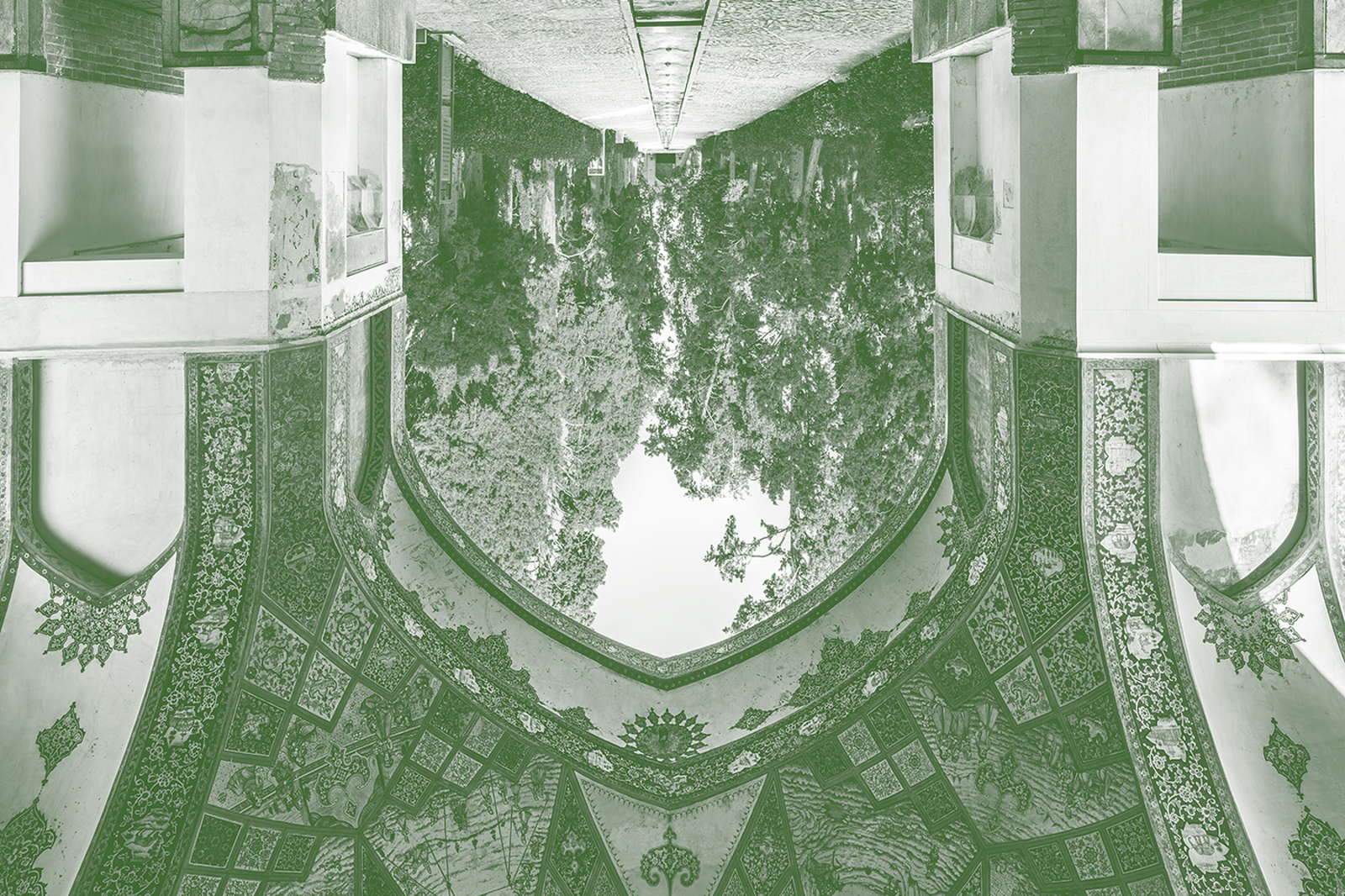

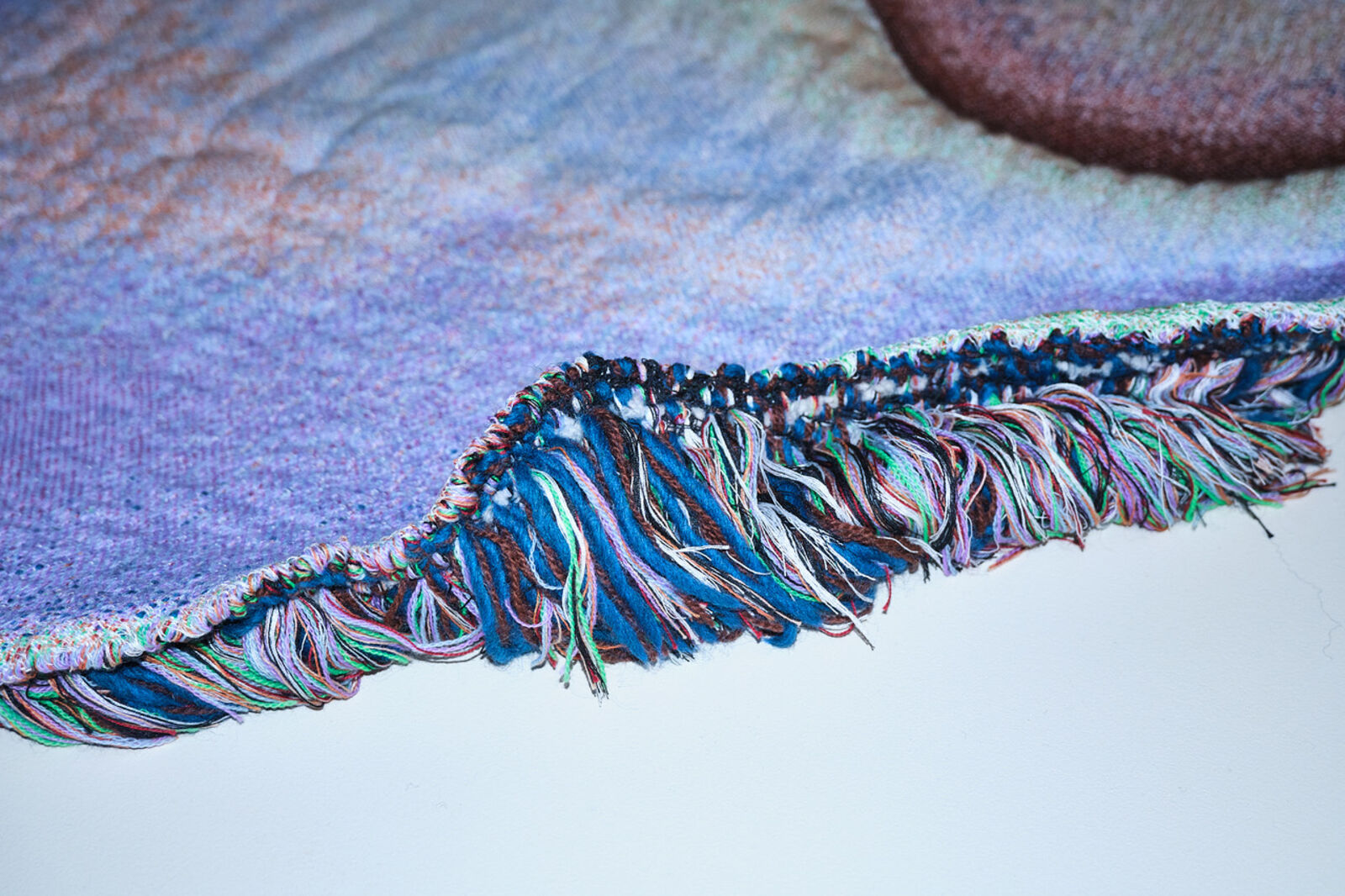

One of the topics of our publication is the tension between water management and resistance, something Maartje Fliervoet has been looking into over the past years. One of her works on display, called Spilleages, is a series of three woven textiles based upon water photogrammes in which the artist focuses on how she tries to ‘control’ her visual language, and on the human desire for control in general. Pouring water on fibre-based photo paper causes it to undulate, transforming the printed water’s shape and hue, such that the resulting prints disconnect from the artist’s intervention. Scans from these prints were woven and their wavy character was translated into the weaving process, resulting in relief-like textile works.

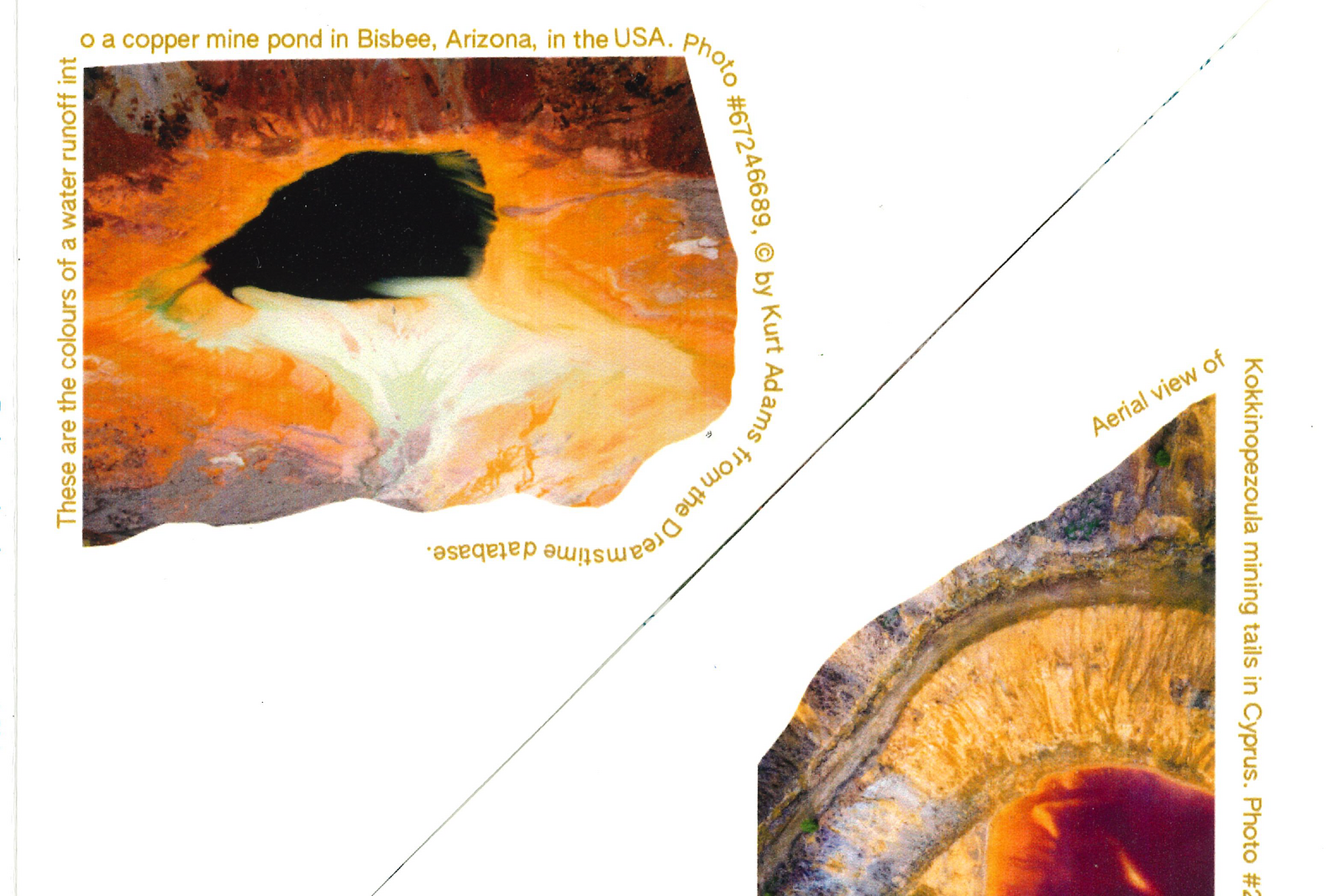

Aside from Spilleages, Maartje developed Site Specific Slurry, a textile print placed on one of de Appel’s curtains, connecting the copper roof of the building to toxic waters from copper mine tailing ponds. While writing on control and resistance, she noticed the inside of a rain-soaked food packaging box from her shopping bag. The original appearance of this geometric container being affected by the water, this evoked an image of a room flooded by outside influences; a scale model for a spatial embodiment of resistance. She then translated this image to the interior of de Appel. This textile work will be on view during opening hours after twilight.

Exploring photography, printmaking, installation, textile, language and printed matter, in her practice Maartje Fliervoet aims to make space for the undefined and the formless as a way of thinking. Her works generally question states of fixedness. In 2015 she initiated Manifold Books in her studio: a project space for contemporary art looking into relations between book space and exhibition space.

While writing on water and its interplanetary distribution, we received permission to include a poem by the poet Elicura Chihuailaf about water from a Mapuche perspective. Notably, the poem’s title Itrofill mogen (“The water of life”) recurs in the subtitles of Seba Calfuqueo’s video work Kowkülen (Liquid Being) from 2020. Composed by an audiovisual recording and the author’s writing, the work goes through a physical, personal and poetic journey regarding water, wetlands, lakes, oceans, rivers and springs. It addresses the body, binarism, gender, sexuality, the historical relationship between water and life, as well as their potential as a living space, necessary to the relationship of all territories. This video will be on view during opening hours after twilight.

Seba Calfuqueo is an artist whose work critically reflects on the social, cultural, and political status of the Mapuche people in contemporary Chilean society. Her expansive practice mobilises installations, ceramics, performance, and video to explore their heritage, feminism, and sexual dissidence. Her work often parses out the cultural similarities and differences, as well as stereotypes, that emerge from the intersection of Indigenous and westernised modes of thought. Seba Calfuqueo is also part of the Mapuche collective Rangiñtulewfü and contributes to the magazine Yene.

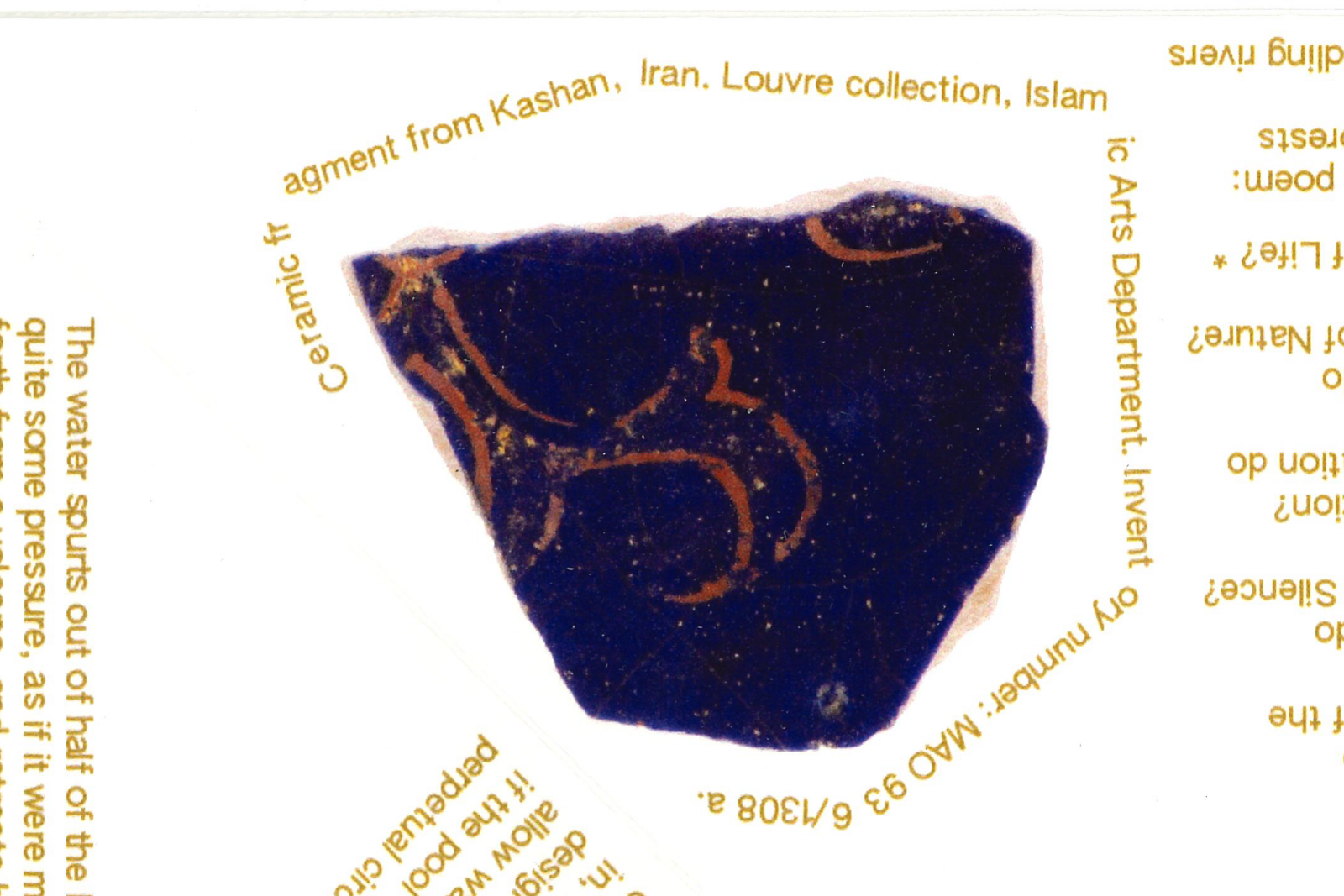

The objects that emerged during the process of writing included artefacts, mementos and relics; things that were connected to our stories. While some of these objects could never be physically found or encountered, others became part of the repertoire of things exhibited in this show. For instance, the Iranian lacquer pen box from the Qajar period (19th century), with the pattern of bird and flower, refers to an old story about public secrets and smuggling miniature artworks. Birds and flowers were adopted as a symbol for lovers in miniature paintings in the mid-sixteenth century, when drawing figures was forbidden. Keeping secrets in public became an important element in our writing. Another fitting example comes from a story about the Hoowz-e-Joosh in Fin Garden (Kashan, Iran), recounting that the bottom of this pool was once covered with beautiful tiles that at some point were stolen. Even though we never found any clue about where they were, a tile from Kashan from another context made its way into the show. On view are also a few Iranian sun inspired textiles that resonated with a hypothesis of water originating from dust emanated by the sun. It refers to mithraism as the sun figure is a symbol of Mehr; an ancient Iranian deity (yazata) of covenants, light, oaths, justice, the Sun and friendship. A female face overlaid on the sun pattern may also refer to Anahita the goddess of water, rain, abundance and victory.

Photo: Sander van Wettum

Photo: Sander van Wettum

Photo: Nikola Lamburov

Photo: Nikola Lamburov

Photo: Nikola Lamburov

Photo: Nikola Lamburov

Photo: Sander van Wettum

Photo: Sander van Wettum

Photo: Nikola Lamburov

Photo: Sander van Wettum

Photo: Nikola Lamburov