Play and disobedience

Conversation between Mercedes Azpilicueta and Lara Khaldi

Detail from CaccHho CucchhA by Mercedes Azpilicueta

Artist Mercedes Azpilicueta and Lara Khaldi, artistic director of de Appel, discuss the works and themes of the exhibition CaccHho CucchhA, in a conversation that grows over the exhibition span.

Lara Khaldi (LK): In our various discussions about CaccHho CucchhA you have framed play as a form of disobedience and emancipation from adult behaviour and time. What does it mean to disobey through play, and how does it come about in the various play objects/costumes/play area/artworks you are making for the exhibition? I realise this is something we will only discover as the children interact with the objects. Perhaps we can reflect on disobedience and emancipation in play and in relation to your work in general, as well as on your project Bestiary of Tonguelets, a reference of this exhibition and where our conversations began with the suggestion to convert the disobedient sculptural characters into costumes for children.

Mercedes Azpilicueta (MA): I think I got into this project thinking about time and performance, two of my favourite materials to work with. In recent years, I have found myself in the studio, doing everything I was meant to do, and asking myself, is this it? A long time ago, I understood that I needed to be contesting the very definitions of what I felt part of. Otherwise, why would we do what we do? And I have the impression that my practice taught me in the last years that play (and humour) are very useful for disobeying the rules. For me, it is important to shape our own ways of doing things; how could we just play the game? I guess part of my work is to make, or rather invent, new worlds, scenes, events. Like immersive environments or spatial dramaturgies, as I have called them before. Whatever that space is, it works as a medium where I can invent my own conditions, my own necessary limits, while at the same time rebel against those structures, and against myself too.

For this exhibition, I wanted to explore ideas of play and disobedience, to embrace the unexpected, the awkward, the failed attempt. Knowing first-hand what it’s like doing things with children, I expected many things to go differently than planned, and there is so much fun, beauty and wisdom in embracing that.

Bestiary of Tonguelets has been a foundational work for me and it is part of CaccHho CucchhA – from previous drawings that are now woven onto a tapestry to leftovers of materials that appear hidden in the new costume-sculptures, like little treasures waiting to be found. Through Bestiary, a play that has not yet taken place, I learnt to think in multiple ways, to collaborate with others, and to translate ideas and things into different media. Bestiary is a constellation of many different pieces, costumes, drawings, videos, sounds, all spread throughout space. My starting point was speaking about outcasts, poets, animals, mythical non-only-human-beings, and the political and socio-economic implications between Europe and Abya Yala. I wanted to (un)learn so many things as a "sudaca"* living in Europe. The characters of Bestiary of Tonguelets (ranging from a cigarette butt, to a Ruda leaf, to a drawing of twin sisters, half-human and half-animal, that came to life) are clumsy, messy, funny, a bit smelly, and, at the same time, their voices sing to us poems of collectivity, of toxicity, of shared knowledges, and of obsolete knowledges that nobody seems to want nor need today. Their decadency pays tribute to a world that is collapsing, an aching world that can only be felt through the senses (and not only human-senses, because everything feels and breathes in Bestiary). For example, smell is one of the key senses in the exhibition, a sense that seems to weave like a spiral spine through all the different works and bits that are part of it. From all the smells that appear "on stage", like beeswax, clay, rubber, blood, mate, coffee, ruda, tobacco, etc, I always think of a particular one, the smell of wet cardboard. That smell also returns to CaccHho CucchhA when I imagine what "cucha" actually means in Argentinean jargon: a dog box, a resting place, a shelter, maybe under the rain, fragile but still carving out that needed space.

In CaccHho CucchhA, the sense that gets amplified is hearing. Here, we bring together a series of costumes that make some form of sound to be used and played with. From old cow bells that vibrate inside chambers of coconut fibre, to wooden washboards turned into güiros, to rain sticks that trickle with cherry seeds inside vacuum hoses. This time, I thought I wanted to research further the potential of making sound through wearables, textiles, and everyday (perhaps some of them obsolete) tools; and with the public as well, of course. The audience becomes the performer in this exhibition but not in the traditional sense of participatory work. Nobody is demanding anything in this space.

Going back to your initial question about what it means to disobey through play, I think playing allows us to (re)create our own worlds, with their own agreements and disagreements; to imagine or create what does not — yet — exist, or to disassemble what needs to be changed and re-built. And most importantly, we do that from the scraps and fragments that we are left with. I feel this is a time, the time we are living in, where we need to rehearse and do that the most, as adults and non-adults, for everyone and anything that comes after us.

*sudaca is a pejorative term in Spanish to refer to people from Latin America.

Mercedes Azpilicueta, Bestiary of Tonguelets, Museion Bozen-Bolzano (Italy)

LK: Thanks for the generous answer, Mercedes. It makes me think of many different things. The costume-characters in CaccHho CucchhA do not seem to be as decadent and depressed as in Bestiary, they are rather more optimistic, active, animal and plant-like. In a conversation about speaking animals, Oxana Timofeeva and Haytham El-Wardany discuss why animals teach us in fables rather than humans: because people teach morals and animals teach wisdoms and perhaps children like (to learn from) animals because they don’t moralise like adults do. How is the visual content of the tapestry brought together in relation to play?

MA: The Jacquard tapestry is made with a sense of play, where images act as sly teasers for the audience. I take pleasure in juxtaposing different temporalities, which creates a chaotic environment, where real and imaginary images, photos and drawings, converge carrying the potential to be used. This means that children are able to place their faces, hands or legs through holes that look like the inside of giant barnacles. Or perhaps they can use the pockets woven into the tapestry, or hang their creations (made during the accompanying public programme) from the handles we cut through the weave. There are pop-up windows that show hidden elements, like labyrinths and characters, that appear in the exhibition space as wearables or costumes. The tapestry also extends in the space as its warp continues on each side of the piece, making it entangled and messy, unfinished and layered. I guess another sense that gets deeply amplified in this exhibition is the sense of touch. I mentioned before the sense of hearing, as the wearables make sound, but touch is equally present in the works, as well as in the tapestry. When I was weaving at TextielLab in Tilburg, together with my long time collaborator Judith Peskens, I was told this is the first time that they were making a piece to be touched and used like this by the public, children in this case. Making this tapestry meant, for me, a new form of emancipatory practice. It meant taking another leap as a maker: to imagine what did not yet exist in my material practice — the potentiality of use, of play, and bending the materials (and the content) to make that happen.

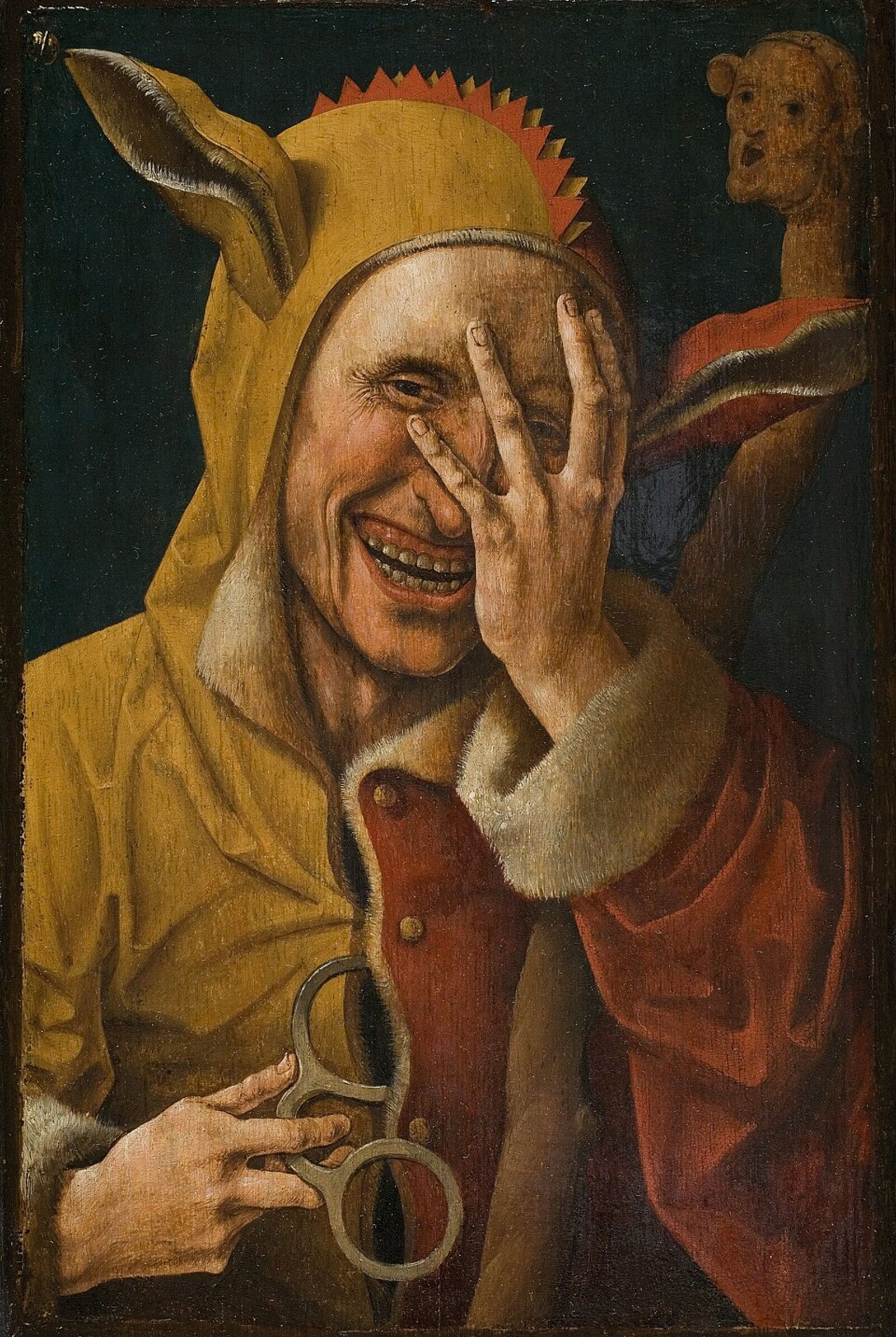

The visual content is a generous abundance of images, as I usually like to work on these types of compositions or assemblages. These assemblages have a fantastical, imaginative quality from a baroque viewpoint that deceives the audience, guiding them to engage with it, and even collaborate with it. And, at the same time, these images serve as mere entry points for deeper interpretations. For instance, you see children in Gaza playing amidst the rubble of a genocide, placed next to images from the second-wave feminist movement in the Netherlands. There's also a tribute to Argentine poet, musician, and writer María Elena Walsh, particularly her song The Gardener's Song. I enjoy placing all these images together in an irreverent dance. You see archival images from Aldo van Eyck’s playgrounds, which reflect how a city should be used, while at the same time, those very playgrounds serve as infrastructure to support the painting Laughing Fool by Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen. The figure of the fool makes an appearance in several parts of the composition. There are drawings of creatures I made back in 2007 like the Yarará-Warrah (also a character that appears in Bestiary of Tonguelets), next to new drawings related to the wearables and characters that are part of CaccHho CucchhA, like the Rainy Slugs or the Rattling Roots. Next to letters from the Palestine Liberation Organization's alphabet, there are archival images of street festivals such as Hartjesdag on Zeedijk, where people dress in costume (often cross-dressing) in a joyful parade that blends medieval traditions with current carnival costumes. Again, all these elements are thresholds, we could call them doors as well, to other interpretations; exceeding the idea of locality as we know it. And the list goes on. There are many birds woven in as well, from the Bernacle Goose, which is one of the foundational mythical stories that gave birth to this exhibition, to storks and medieval bird creatures. There is a photo of my child playing with an empty bucket in Buenos Aires, near Handala, and archival images of Dutch children celebrating traditional folkloric rituals. There are many references to The Flora Batava, an illustrated overview of all Dutch plants, mushrooms, mosses and algae known in the 19th century, next to current images from the garden outside de Appel, or images related to the Situationist art movement Provo, such as children jumping on sleeping bags, a photo that inspired the costume Jumping Bernacles.

Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen, Laughing Fool

LK: How do you think you’ll “use” the tapestry with the children in the storytelling and weaving playshops?

MA: The tapestry is meant to be used as an open book, a source, where you could pick an image to continue its story. On the other hand, weaving is such a beautiful, haptic technique during which we share and exchange knowledge and words. You weave and the act of weaving goes hand in hand with the act of speaking or singing. Also, by being able to peek behind the tapestry, you access the other side of the stories that are being told. What could they mean looking through a different lens? I could imagine that in some of the playshops that we give, children could weave themselves, and perhaps some of those explorations could be connected to the tapestry. Could the weave continue growing throughout the exhibition space? Could it grow in a rhizomatic way? From its edges, fringes that touch the floor, could those be extended with other yarns and weaves? I am curious to see how the work (and stories) could keep on growing and changing. This reciprocity with the audience is also something I had to imagine differently within my own practice, and taking that leap (and risk) feels very liberating.

LK: You mention how the decadency of the characters in Bestiary ‘pays tribute to a world that is collapsing’. I would say that our world is indeed collapsing, and we speak of this often: that we somehow continue to play in a world that is collapsing around us. One of the images you use in the new tapestry in CaccHho CucchhA is of children in Gaza playing in the middle of the genocide's rubble. Play becomes an emancipatory practice, also in how you describe it as ‘imagining what does not yet exist’. Why do you think we need to insist on addressing difficult issues (of struggle, of colonialism, of immigration) with our children, particularly in art works?

MA: I feel we need to address difficult issues with our children because the world we live in is full of challenges and complexities. Pretending that we live in a fair, simple world would be a farce. I want my child, and every child, to be able to navigate the challenges they will inevitably face in their future. And nothing needs to be sugar-coated. In a world marked by injustices, privilege should be acknowledged. I was lucky to grow up in a household where, thanks to my mom's work as a social worker, I was aware that other children lived very different realities. She would take me and my sister to play with kids who had been removed from their homes due to domestic violence. It was tough to face that as a child, but it taught me important lessons. I had a happy childhood, but one that was also in contact with the public health system in Argentina, where poverty affected nearly 50% of the population in the 1980s and 90s. Visiting my mom at work in the public hospital (she cared for teenage mothers and children), and my dad as well (as a paediatrician and neonatologist), shaped me profoundly. I was constantly immersed in (other) realities. Today, my work is different. Through artworks, I can approach difficult issues — struggle, colonialism, gender inequalities and immigration — in a more subtle, imaginative way. Through an installation, a spatial dramaturgy, a performance, an event, I can propose and tease the audience with a myriad of possibilities that continue expanding in unimaginable ways through their experience and interpretation. And most importantly, those possibilities give the audience the chance to practise change, to re-invent something anew, something that perhaps we haven't thought of (yet).

LK: You also take the barnacle goose as a central fable in the work. Perhaps you’d like to reflect on that a bit?

MA: The Barnacle Goose myth is an old story from this region — Northwestern Europe — about a goose that would migrate to the Arctic to nest and reproduce, only to return later in the year. In medieval and early modern times, people would see these geese walking or flying around, yet could not understand where they were coming from. Out of this mystery came the idea that the geese were not born in distant, unreachable lands, but instead grew from barnacles attached to driftwood or trees by the water’s edge.

Barnacles, being crustaceans, have feathery protuberances or extremities that extend from their calcareous shells, and these were imagined as the beginnings of wings. In some versions, people even described seeing half-formed geese “hanging” from the barnacles before dropping into the water, as if they had ripened and fallen like fruit. This image of geese ripening like fruit is woven on the tapestry. The story was so persistent that, in parts of Ireland and Scotland, the goose was considered a kind of fish rather than a bird. This meant it could be eaten during fasting days, when the eating of meat was forbidden, but fish was allowed.

Beyond its strangeness, the myth carried deeper notions — of migration, of journeys beyond our known world, of the difficulty of imagining life cycles that unfolded far away and unseen. It was a way of explaining absence and return, of giving shape to something otherwise incomprehensible. Through such tales, children are introduced not only to the mysteries (and magic) of nature, but also to the ideas of migration, transformation, and belonging.

LK: You write that experimenting with the tapestry (in how it is more porous and open-ended) has marked a more emancipated form of artistic practice. I guess this comes out of the need to share the work with others, not only as a finished work, but as a work in progress and in conversation with others. I was wondering about the sculptural costumes and how in conversation they became instruments that are multisensory and intentionally open-ended. Has it been a struggle for you to balance the formal aesthetics of your practice with the intended interactive and performative use by the children? Was it difficult letting go of certain aesthetic or formal considerations? And while conceiving of the sculptural costumes, why do you see a need to create materials that produce sound, invite movement, or evoke particular sensations?

MA: I can say it has been an exciting challenge to make the work interactive and performative. This meant privileging certain qualities such as functionality, sturdiness of materials, and the possibility of working in multiples. It was not about investing everything into one “perfect” piece, but about creating abundance — five, six, seven pieces that could be shared and used simultaneously by the children. I remember a conversation in a mentoring session with educator Daniela Pelegrinelli, who has been guiding me since last year, about pedagogies of disobedience, theory of play and this idea of multiplicity. I was struck by it: not only did I have to imagine pieces that could be activated and worn, and misused, but I also had to imagine them in series, in multiples, as a small community of objects.

Colour became a central visual element for me, as well as the crafting and the presence of specific tools I wanted embedded in these wearables. Together with designer Lucile Sauzet, we conceived seven sculptural costumes — modular and interchangeable, combining different materials and textures. As in our previous collaborations, we gave priority to crafting with our hands, to the doing. All of the pieces were made with sustainable or repurposed materials: coco fibre, cherry seeds, and fragments carried over from earlier works of mine. Alongside these organic or handmade elements, the costumes also include industrial materials such as velcro or socks, as well as repurposed crafted objects from another time, like cowbells that once belonged elsewhere. Some of the wearables incorporate tools that would usually serve another function: washing boards and clay tools, which in this case become part of the güiro inspired wearable or costume, the Scraping Cicadas. The Scraping Cicadas take inspiration from the song by María Elena Walsh, Como la cigarra (Like the Cicada), the story of a creature who, after a year underground, emerges as a symbol of survival and defiance. The song conveys the idea of being repeatedly "killed" or facing adversity, yet still emerging to "sing to the sun" like a cicada that survives after a long time underground:

"So many times I was killed many times / I died nonetheless I'm still here coming back to life / I'm grateful to adversity and the hand holding the knife / for it did a bad job at killing me / And I carried on singing. ... / Singing to the sun / Like the cicada does after a year under the ground (...)"

I felt an urge to work closely with sound. All of the costumes produce sound, most of them percussive, specifically idiophonic instruments, bells, gongs, rattles, that vibrate when struck, shaken, or scraped. I was interested in how the body could become a sound-making instrument, how movement could generate resonance. The performative has always been at the core of my practice, but here I take an extra leap by inviting the audience to activate the pieces themselves. I wanted to see how the costumes constrain movement, how they alter the way we inhabit our bodies, how they shift our sensations. At the same time, I wanted the collective dimension to be present. The sound and movement emerge not in isolation, but through a group, through the presence of others, through listening and responding together. It is in this shared experimentation that the work comes alive.

María Elena Walsh - Como la Cigarra

LK: I’ve also been thinking about the role of the tapestry in this project. I see it as existing somewhere between an archive, a landscape, and a playground of meanings. I was struck by the way you describe the images, drawn from different histories and cultural contexts, as thresholds: a threshold as both a door into another world or into a set of meanings, but also as a point of transformation. Those captured moments of rebellion, joy, and refusal suggest transformative potential in life itself. Yet weaving them together might also risk advancing a universalising truth about play or emancipation, or even neutralising their force — not only by combining the images, but also through their aestheticisation within the tapestry. Is this a tension you have considered? I recall you being cautious about aestheticising suffering or genocide. On the other hand, tapestry as a medium carries a history of weaving together collective stories and common histories. How do you negotiate these different aspects — between aesthetic form, collective practice, and the ethical weight of the images?

MA: I see the need to work with images and representation because I find in this task the potential to transform and to give life back to images. Many of the sources I work with come from books or archives that I have to physically visit or request permission to access. For me, it feels important to take these images out of that closed, institutional realm, to un-do them and bring them into the foreground — playfully, even irreverently. This irreverence, this mischievous way of handling images, this un-doing, resonates with how disciplines themselves tend to operate, with their hierarchies and codes of expected behaviour. Interdisciplinary work is pivotal in my practice, and to really enter that space in which something has to shift — some tension or “out of the normal” needs to happen.

At the same time, I am cautious about what types of images I choose. There is a careful selection process of what I feel can live together, or be woven together, without neutralising nor universalising each other. I want to acknowledge and give space for all singularities and differences; even though all images are woven together, through the same warp on the loom, each holds onto its own act of (re)presentation. This research, the sourcing and choosing of images meant spending time with specific archives, making sure that what was picked was aligned with the principles of the work. It was a fruitful process done together with Laura Kneebone, who worked with me in this careful search. I wouldn’t feel comfortable weaving images that directly portray suffering or genocide. That’s why, for instance, I chose images of children playing in Gaza — moments of vitality and resilience, even when set against, being immersed in, a disastrous reality.

And here the tapestry itself becomes significant. The tapestry is never a neutral surface — it carries with it a long history of weaving together collective stories, whether celebratory or commemorative, and of making images public, visible, and shared. In that sense, the medium itself insists on the collective. But I am also aware that by aestheticising images there is always the risk of softening their force, of universalising or flattening the very differences that make them powerful. I try to negotiate this by working in a way that keeps the images porous, in conversation with one another, never fully resolved. I think of them less as fixed symbols and more as thresholds — openings into other stories, other meanings, other possibilities of transformation.

So the tension is always there. I don’t really try to resolve it, because in a way that tension is the work — it even demands a kind of new ethics and aesthetics. I think of it as an ethics and aesthetics of undoing, while still exposing (or even overexposing). I have the impression that for any undoing to really happen, the ethics and aesthetics themselves need to carry weight, to have value, to manifest and take form.

I mentioned earlier how I often draw inspiration from the Baroque. This takes me back to when I was teaching Aesthetics at the Universidad Nacional de las Artes in Buenos Aires, in my twenties. From a Latin American perspective, the “New World Baroque” is something quite particular — it comes out of transatlantic colonisation, slavery, and processes of transculturation, while at the same time laying down the shaky foundations of a failed Modernism. I often return to the words of Cuban poet and critic Severo Sarduy, who wrote that “to be Baroque today means to threaten, to fool, to parody the bourgeois economy, to attack the stingy management of wealth at its very core: the space of signs, of language, the symbolic base of society… To overspend, to squander language only for pleasure—and not for information as in domestic use—is an attack on common sense, on morality, on what is considered ‘natural’.”*

For me, this idea of the Baroque offers a way of thinking about how we deal with images and meaning today. The so-called ‘return of the Baroque’ is often described as a reaction to unfinished histories, to the constant production, performance, and erasure of identities. Some see Baroque elements as an ethos, one that interrupts the tendency to fall back into order, clarity, and singular truths. Others understand the Neo-Baroque as signalling the crisis of an unfinished modernity. What interests me is how the Baroque refuses to settle: it prefers frantic rhythms, instability, polydimensionality, a kind of regulated disorder or planned chaos. It takes pleasure in proliferating meanings, in substituting one metaphor for another, in obscuring fixed meaning rather than locking it down.

That way of working opens up possibilities for the tapestry — it allows it to be at once a body of multiplicities, an archive, a landscape and also a playground of signifiers, metaphors, and meanings. All this translates to me as a kind of generative force that by sustaining itself creates movement for others.

* Severo Sarduy, Ensayos generales sobre el Barroco, Buenos Aires, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1987

LK: Your take on the New Baroque is very interesting, and I see how you borrow both media and method from it. Still, the work circulates within the contemporary art economy, where it becomes aestheticised and captured in ways beyond our control. I often wonder whether artists can protect their work from this process, or if such protection is even possible. But perhaps that is a conversation for another time.

MA: Yes, this could be an important conversation to have. For now, I can say that once a work enters circulation, especially in today’s hyper-mediated image economy, it inevitably acquires layers of meaning and value beyond the artist’s control. In fact, this uncontrollability might be intrinsic to any contemporary practice, and, at the same time, it echoes the Baroque excess I mentioned earlier, where images spill over boundaries and resist containment. Rather than resisting aestheticisation or capture, one could think of the work as navigating those forces, sometimes even amplifying them or making their mechanisms visible. In that sense, “protection” might not mean shielding the work, but instead shaping the conditions of its circulation. What becomes possible is something closer to what Saidiya Hartman calls critical fabulation: working within the inevitability of circulation, but reframing and redirecting it, so that the work can unsettle the conditions of its own capture. In other words, rather than trying to protect the material from being consumed, to re-narrate, reframe, and re-imagine it, exposing the violence of circulation while opening space for alternative meanings.

LK: Let’s return to the exhibition. We have often discussed the role of adults in this project. At first, you imagined their absence, concerned that parents might interfere with children’s free play or playshops in disruptive ways. But gradually we came to see their presence as essential, not only because parents can learn from their children, but also because play is not limited to childhood. Adults, too, continue to play in different ways throughout their lives. Would you like to reflect on your conversations with Daniela around this?

MA: Our conversations began last autumn, almost a year ago. I met Daniela through a mutual friend, and I was very lucky for that. Daniela has a background in Special Education and Educational Sciences from the University of Buenos Aires, and coincidentally, we also come from neighbouring towns in Argentina, a nice reminder of how vast yet small the world can be. Daniela introduced me to different theories of play, radical pedagogies, and disobedience. Thinkers like Johan Huizinga, Brian Sutton-Smith, Roger Caillois, Gilles Brougère, as well as closer references like Chiqui González or the Grupo de Investigación en Juego from the Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina. With her guidance, I came to position myself within a rhetoric of play that understands play as imaginary, promoting worlds and symbolic making, as well as play as identity, as ritual, and as a practice that fosters cooperation, community, memory and resistance.

Words are not enough to express what Daniela has meant for the making of this exhibition. We worked online every two to three weeks: she mentored me, gave me reading materials, suggested authors, and also gave me homework. For example, she would ask me to visit every children’s activity in Amsterdam with my own child, not only to observe how children behave, but especially to notice how the mediators behave. She asked questions like: is there space for children to design their own itinerary? How freely can they move? Too often, children are seated on the floor, listening passively to an adult explaining something to them. She even asked me to experience the exhibition space at de Appel differently, getting down on my knees and walking on my hands to see from a child’s perspective.

Daniela has a very material approach to play. She sees how children are raised today as a way of inserting them into a capitalist society. She helped me understand that our gaze on children is tied to the idea of progress. Instead of seeing them for who they are, we see them for what they will become. Today, childhood is valued only for its utility, when in fact it should be useless. She also takes a critical stance toward “progressive pedagogies”, which have become a market of their own. It seems as if we want children to play in order to learn something, or to become autonomous. But autonomous for what? In such individualistic societies, what we actually need is to reinforce the collective.

She introduced me to radical pedagogues like Loris Malaguzzi and the Reggio Emilia approach, the “serene school” of the Cosettini sisters in Argentina, the idea of “useless knowledge” by María Eugenia Villa and Jorge Daniel Nella, or Jean Le Boulch’s psychomotor pedagogy, which places movement at the centre of learning. This deeply influenced how we imagined both the costumes and wearables and the exhibition for the public, where movement was crucial and at the core. I started to think about the kinaesthetic experience, something I had already been exploring in Bestiary of Tonguelets: textures, smells, sounds.

We talked a lot about time, the fragment or cacho of time, and the Greek concept of aion, time as intensity, unmeasured, the time of childhood. And we talked about the untamed frontier, that threshold, that rupture, that entrance, that cannot be domesticated, that does not adjust to the pressures of the context. The cucha, as that magical circle, that is the space of playing. We tried to define play as an emancipatory act, one that exists only in the service of play itself.

As an adult, Daniela also asked me to return to my own childhood memories, something I later shared at our reading group as part of the process of preparing for the exhibition. I came to see that what we wanted to create was a collective experience for children and their caregivers. That was the difference from daycare, school, or after school activities where children are left behind. We wanted to create opportunities for parents and caregivers to get involved, to play, to observe their children playing.

We focused on play as a communal ritual, and on how the exhibition space could resist the logic of the school. Because to imagine new worlds, there has to be disobedience. If play is to be emancipatory, it must also be disobedient. And also, what kind of disobedience? For adults, perhaps it is the invitation to play in useless, unproductive ways. I wanted CaccHho CucchhA to be a reminder for adults that play is still possible, and necessary. Because play allows us to meet one another beyond who we are. Play connects and creates a shared language, a space that daily life does not offer. And I believe we, as adults, need to play more in order to un-do ourselves.

LK: Perhaps some of these adults will even want to play in the playground structure you developed with Katha, inspired by Aldo van Eyck’s playgrounds. His neighbourhood-based designs in Amsterdam created open, public spaces for all children, and unlike conventional models, his playgrounds emphasised decentralised composition and imaginative, multifunctional spaces that encouraged creativity, social interaction, and open ended play. How have you engaged with his basic designs, and what alternative elements did you introduce, and why?

MA: I am one of those people who lights up whenever I come across one of Aldo van Eyck’s playgrounds in Amsterdam. Sometimes I spot one from far away while riding my bike, and I can’t help but smile. I feel he managed to reclaim so much space in the city for children. His playgrounds are so open-ended that, even as an adult, you can still place yourself inside them, step into those structures, and feel invited to play. The tapestry has some of them in its composition.

With Katharina, we wanted to take that spirit of openness and re-imagine it for the exhibition. Van Eyck’s designs are very minimal, simple geometries that suggest infinite possibilities, and that simplicity was important for us. But we also wanted to expand on the idea of transformation: our structures can be a playground, but also a skeleton for tents, shelters, or temporary dwellings built by the children themselves. In this sense, they become a cucha, a home, a threshold, a small protected space that children can inhabit, reshape, and claim as their own. It is a place of intimate play, but also of collective making.

Unlike van Eyck’s more permanent materials, our tents require tending and attention. They can be dismounted, reassembled, rebuilt, constantly evolving with the children’s interactions. In this way, time becomes a material of the work: each action leaves traces, extends possibilities, and transforms the space. The exhibition is never fixed; it grows and changes as play unfolds, carrying the memory of past activities while inviting new ones.

Next to taking inspiration in the playgrounds by van Eyck, we also worked with the anatomy of the barnacle, a key figure and character in the exhibition. Children and adults encounter structures and forms that draw on the hermaphrodite body of the barnacle, its ovaries, its cavity, its eggs, eyes, stomach, mantle cavity, nerves, and cirri (its feeding legs). To make these pieces, we re-used works that Katharina and I had previously created together for an exhibition at Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein in Vaduz, in 2022. That project, which I titled Kinky Affairs at Home, was entangled with my first experiences of motherhood and the challenges of those first months, brought into dialogue with the work of feminist artist Anne Marie Jehle, a punk figure also linked to Fluxus, whose art and life were deeply intertwined.

The idea of re-purposing some of those earlier wooden works felt very natural for this exhibition. There is a constant sense of continuity in the work, as one project flows into the next, carrying traces of past experiences while opening into new forms.

Iglo playground by Aldo van Eyck, Vondelpark, Amsterdam

LK: At de Appel, we are more interested in the use and activation of artworks than in their purely contemplative form, so we asked you to collaborate on a workshop programme together with artists who could activate the space for children in different ways. We also initiated a reading group with the hosts of the exhibition and others, reading all the references on play from Daniela in order to think through how to host children. How has this process been for you so far? We have been discussing how to structure workshops in ways that do not over prescribe ‘play’ or dictate how children should interact with the objects. How do you imagine this guidance unfolding? Perhaps you could speak specifically about the weaving workshop you are developing with Anna and Gļeb(s)?

MA: It has been a wonderful experience to plan the different workshops for the public programme, and to have our reading groups regularly. I feel these meetings gave us the opportunity to come together periodically and discuss ideas around education, disobedience, playwork, and unproductive time. We also shared our own childhood memories, and those of our close ones. In a way, I feel we built a small, affective archive related to play. And next to that, we also had many conversations about un-learning how to guide a workshop, how to play with children, what to expect, and how to let them abandon the activity or withdraw, if necessary. We did a lot of that un-learning. I think it was also great to have the insights and guidance from playworker Penny Wilson and her Playwork Primer.

For the textile workshops, I am excited to be collaborating with Anna and Gļeb(s). Anna, Gļeb(s) and I thought we could perhaps approach the concept of weaving in a playful way, by interacting with local wool, cut-outs and other re-purposed materials and by combining them with performative aspects, storytelling and the use of the voice. Both workshops are connected and pick up or follow up on each other’s activities. In that sense, the two processes are closely connected. We also discussed how the weaves could later be shown in the exhibition space, perhaps in relation to the tapestry as extensions or prostheses. We have talked about felting and embroidering as well. I find the idea that a collective activity unfolds across different groups and moments very interesting and even necessary. So, not looking for a concrete result right away but rather being a witness to a broader picture or experience that keeps on unfolding and evolving over time, through multiple hands, perspectives and energies.§