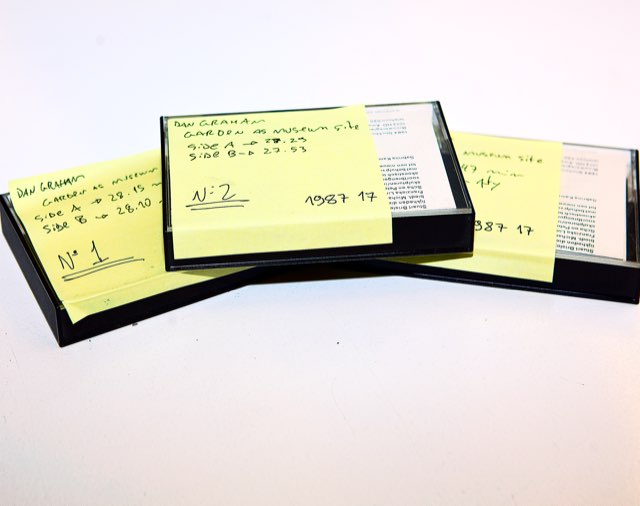

Dan Graham "Garden as Museum Site"

de Appel, Prinseneiland 7, Amsterdam

© Hans Sonneveld

© Hans Sonneveld

© Hans Sonneveld

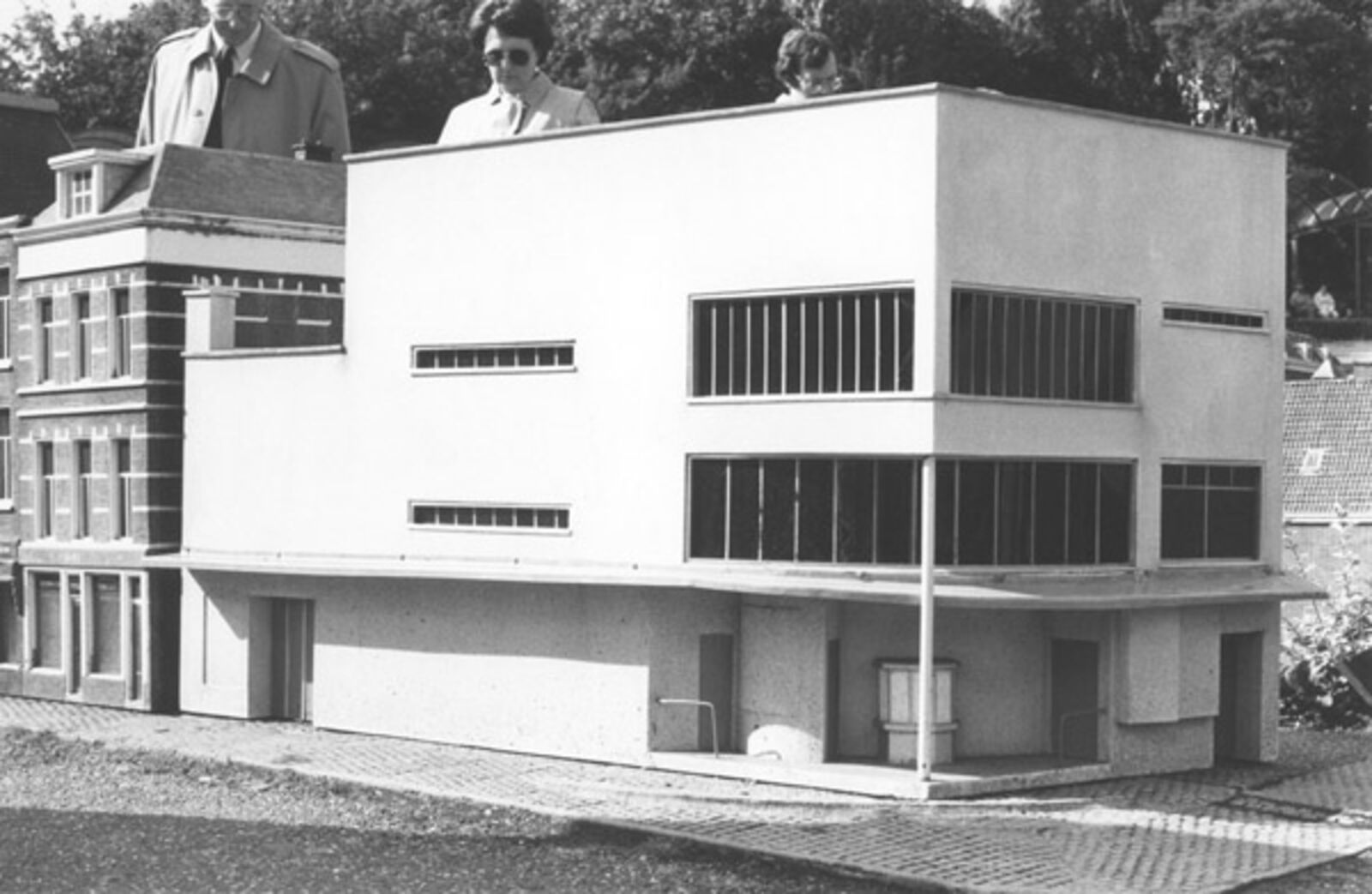

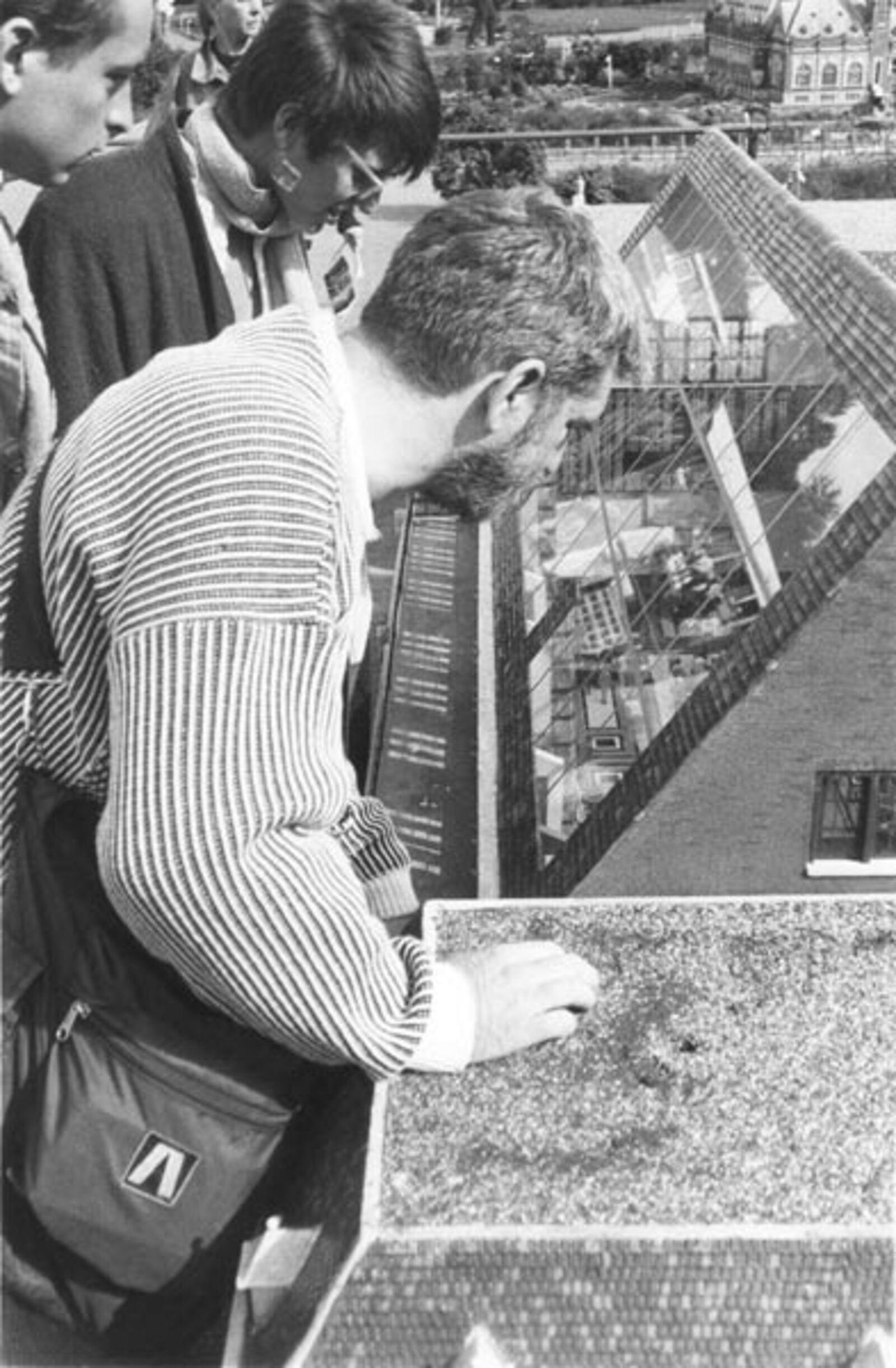

‘Ten years after confronting the public with its mirror-image in Mirror-audience at De Appel’s former space on the Brouwersgracht, Dan Graham was back. His lecture The Garden as Museum Site on the 27th of September was subtitled from the Italian Renaissance garden through the New York city corporate atrium garden to Parc La Vilette as educational theme-park. The erudite lecture, criss-crossing history and enlivened by excerpts from Rem Koolhaas’s Delirious New York, film images of Coney Island and recent examples of New York’s glass office architecture, offered many lines of approach which, like a prism, lead back to Grahams fascination with reflection, glass and the place of the viewer. At the same time the lecture provided background to a number of activities which took place on Prinseneiland this year or are planned for next year. Graham’s Cinema from 1981 was shown in June as part of a presentation of architectural models featuring film and photography, under the title Cinema Objects, with work by amongst others Tony Brown and Rodney Graham. During a lecture about this Theatergarten project, which was partly inspired by the work of Dan Graham, Rudiger Schottle talked about the Cinematheater ins Grüne for which Dan was to build a scale model. A work that was originally to be produced by De Appel, Pergola/Conservatory which refers to the ancient Roman bower and to 19th century greenhouses, was realised in September at the Marian Goodman Gallery in NewYork. Has Dan Graham become an historicizing artist with encyclopaedic interests? With the presentation of the Theatergarten is De Appel now involved in garden architecture? All loose ends came together in Graham's lecture and certain areas were clarified which currently concern a number of contemporary artists. The argument started with the history of the 'themepark'. The Baroque garden, initially an elegant intellectual game for a cultural elite, became a public park in the 19th century which meant that its narrative ‘discourse’ disappeared. In its place came the Rousseau-inspired enjoyment of nature, in particular its picturesque aspect. When ruins and grottos make their appearance they are no longer fragments of a world view as they were in Baroque times, but painterly motifs or ‘follies’. In the 20th century ‘theme-parks’ like Coney Island on the outskirts of New York, the spectacle of film is included; inspired by stage-sets, spectacular events were mounted such as a large building going up in f1ames in amusement parks like Disneyland and Universal Studios these filmic events are the main source of enjoyment. While the natural park has its cultural opposite in the theme parks with their filmic attractions, the new office architecture (known as ‘corporate structures’) is offering a new form of public space to replace parks which have now become too dangerous. Designed with space-age technology, these glass-walled atriums, or indoor gardens, full of plants and trees, with express elevators, are the new havens of refuge for city workers. The high-tech aesthetic of the 60's, softened by the ecological awareness of the 70's, provides a new environment where employees can consume their plastic-wrapped food under the palm trees. Video cameras behind the glass walls keep watch on everything and everybody; safe lunch. Since creating a public amenity is tax-deductable for big companies, the number of ground-f1oor 'public' areas has increased considerably. This has resulted in a strange reversal; the 'theme-parks' have changed from Baroque theatre gardens, via English landscaped parks, to science and educational parks (like Parc La Villette in Paris), while large bank buildings hide behind curtains of greenery. Both of them offer decors for leisure. Graham's recent sculpture and architectural projects should also be seen in the light of these developments that he outlined. Not so much as a critical reaction (Graham would be happy to carry out a big commission in such a gleaming bank building, as he does not share the 'Haacke point of view' as regards sponsored art), but as a reflection on what he sees going on around him. In this reflection he remains faithful to the basic principles that he has employed in video installations and live performances; the spectator sees himself as in a film, via a moving mirror image, sometimes in combination with video images. In the recent sculptures, such as Two Pavilions, Oktogon für Münster and Pergola/Conservatory, the visitor can project himself into the audience by means of a two-way mirror system and see himself objectified, as an actor. Anne Rorimer has described the Pergola/Conservatory as a 'longitudinal open-sided arched walkway with a glass ceiling. By walking through it the spectator literally participates in the work rather than simply looking at it (…). The two-way mirror anamorphically reflects the bodies of multiple spectators when they are inside the work looking up, giving them each extended images of themselves on the curved surface of the ceiling.' Graham himself compares the gaze that the viewer directs at himself with Baroque painted ceilings in churches and palaces instead of putti and madonnas he now projects his own image amongst the continuously changing cloud formations. Visilble through the semitransparent mirrors. In the 1981 model for Cinema, based on Duiker's Cineac building in Amsterdam, he applied a similar principle: the auditorium faces a transparent screen set into the corner of the building. Thus not only does the cinema audience see the passers by on the street as a vague image through the film, but the pedestrians are also involved in the spectacle since they are able to see the static audience in the auditorium through the film projection. In his maquette for the Theatergarten (a project being prepared by Rudiger Schöttle from Munich in collaboration with a number of artists, which will be presented at PS 1 in New York, the Centre Pompidpou in Paris, and De Appel in Amsterdam), Graham goes a step further as well as a step backwards in history. The Cinematheater ins Grüne is based on the position that theatre occupied at the time of Louis XIV, as shown by Rossellini in his film The rise to power of Louis XIV. The cinema is extended into a proscenium looking like a theatre. The pedestrian again sees the back side of the film screen, but at the same time he is turned into an actor by being 'displayed' on the proscenium for a different audience than the one in the park. This old Baroque principle, blended with a filmic decor, is an aspect that also appears in films and theatre the audience under the spell of the performance, becoming itself the subject of a second audience when the theatre curtain is removed (Bunuel’s Charme discret de la Bourgeoisie, the Theatre du Soleil's version of Klaus Mann's Mephisto). Works by contemporary visual artists are also closely related to those of Graham. Jeff Wall's 1979 piece Movie Audience depicts a staring cinema audience. Wall, who is making a deformed reflecting skyscraper for the Theatergarten, shares a number of common interests with Graham, about whom he has written various articles. There is not enough room here to discuss the whole Theatergarten project, but it is worth noting in this connection the frequent use of transparent and moving images Some of the works consist of slide projections (Schöttle), mirror and film projection (Klingelhöller), transparent layers of screened glass (Kemps) gates of perspex (Fortuyn/O'Brien), or an underwater crystal cave (Coleman). It is clear from this project and from the work of the artists mentioned how contemporary materials and media can be appropriated in order to represent the experience of an urban environment with its reflections of shifting cloudy skies and street traffic.’ (Saskia Bos, ‘The Mirror Zone’, De Appel, (1987) 2, pp. 3-8.)